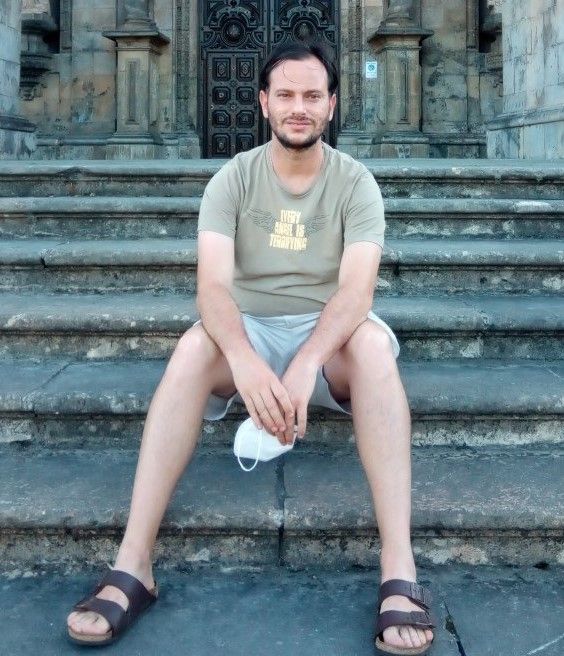

On November 27th 2020, a group of young artists and intellectuals were supported by scores of citizens in a civil protest outside Cuba’s Ministry of Culture. The reason for the protest? To show solidarity with members of the San Isidro Movement, who had been evicted by police when holding a hunger strike at visual artist Luis Manuel Otero’s home, in Old Havana.

The protest – that came to be known as 27N in modern-day Cuban history – has had important wins for the island’s civic movement. This article focuses on determining the protest’s contributions and complexities, as well as assessing its influence on subsequent political events.

The second half of November 2020 was marked by different displays of solidarity from different Cuban civil society groups, who expressed themselves with open letters – both on the island and in the diaspora, communicating their concern for the situation of those holding the hunger strike. After the raid on the house on Damas Street, outrage on social media spilled into the public space. But the lead-up to the sit-in outside the Ministry of Culture reveals the first thing that encouraged civic engagement and the creation of movements in Cuba’s intellectual and artistic fields, especially of young people.

The network shared many common points: the effects of state-led censorshop on their creative work and research, participants coming from official academies (especially Universidad de La Habana and Universidad de las Artes), generational hyperconnectivity, migration of workers to other forms of unemployment outside the State’s control, very little credibility in the Cuban political regime’s discourse. Add to this the fact most participants were fed up, and aged between 20-40. I also need to point out the widespread dissatisfaction among citizens with regard to the national crisis, which became worse with the COVID-19 pandemic.

But beyond the way things happened (which I’ll leave for another article), 27N stands out because it was the starting point for citizens to continuously occupy public spaces in Cuba, and it partially ended with the protests in the summer of 2021. It’s also worth pointing out that the political event established a challenging face-off between the artistic/intellectual community and institutionalized power in Cuba. A group of citizens, who weren’t part of a political movement, were able to sit down at a political negotiations table with a high-ranking official. There’s no doubt that this set a precedent in the totalitarian State.

Another of 27N’s contributions is the fact it forced media coverage of the event, even though the Government tried to discredit and defame its leaders. It also planted a seed that ended up becoming a protest that took the Communist Party completely by surprise. The above forced the Cuban Party/State to publicly recognize an act of political dissidence. One thing that was driven home in popular opinion after July 11, 2021, – especially among young Cubans – was the regime’s inability to provide a political response that would meet protestors’ generational and sectorial demands.

The political system in power in Cuba launched a vast slander and exposure campaign using the media – the press, programs to discredit leaders on national TV and even a revolutionary reaffirmation ceremony in Trillo Park. The Government’s course of action led to a wave of political outrage among the population, which led the Cuban Government to step up its army of cybersoldiers (called ciberclarias “cyber-catfish” in Cuban slang).

27N should be seen as a reaction to political violence and not as an event that would come to mark the end of Cuba’s totalitarian State. In fact, the sit-in of protestors outside the Ministry of Culture that day could have given way to escalated violence, just like what happened in Tiananmen Square.

The citizen-led sit-in proved two things: the lack of expertise in negotiations – something that is acquired over time and with political training -, and the appearance of new leaders within civil society – who will play a decisive role in subsequent citizen-led events, from 11J, the Civic March on November 15th 2021, to the training of civil society organizations, both on the island and in the diaspora. Even so, despite gaps in negotiation prowess and the heavy police presence deployed to surround protestors, 27N proved participants’ restraint and group work, managing to reach a concrete agreement with the Ministry of Culture, even if it was then rejected and boycotted by the authorities just days later.

One of the sit-in’s contributions that is ignored a lot of the time, is the repoliticizing power it had on Cubans living on the island and emigres – especially among young people who had left for professional or educational reasons. This sit-in might be an everyday practice in any liberal democracy, but in totalitarian Cuba, it became a civil feat that has influenced the mass dissent that citizens then led months later. A study carried out by the author of a group of sentences of protestors on July 12th 2021, in Güinera, reveals a high number of participants were aged between 18 and 40 years old.

The sit-in on November 27, 2020, has been taken lightly on many occasions and platforms (from anonymous profiles to a space on Twitter). It has been compared to political events that have unfolded in similar or remote socio-political situations, without analyzing the peculiarities of the Cuban context. However, history and political science prove that contexts are variants and can hold different social catalysts. For that reason, 27N should be seen as a movement and the beginning of a citizen-led cycle of activism, not as a concrete action that would end over six decades of totalitarianism just like that.

This article was translated into English from the original in Spanish.

Comments

We moderate comments on this site. If you want to know more details, read our Privacy Policy

Your email address will not be published. Mandatory fields are marked with *